[ad_1]

For farmers to profit from the post-harvest grain market, the price they receive after harvest must exceed the price they receive for shipping at harvest by more than their storage costs. Evaluating these marketing benefits is complex. The price received is not necessarily the cash price on the date of delivery because farms can transfer and sell grain for delivery on almost any date in the future. This article examines corn and soybean postharvest marketing performance using farm-level data on realized grain sales from Illinois Farm Business Farm Management (FBFM). I consider the allocation of marketing profits by comparing the price a farm receives after harvest to the price the same farm receives at a near-harvest sale in the same marketing year. It is a measure of the total return realized in the post-harvest grain market.

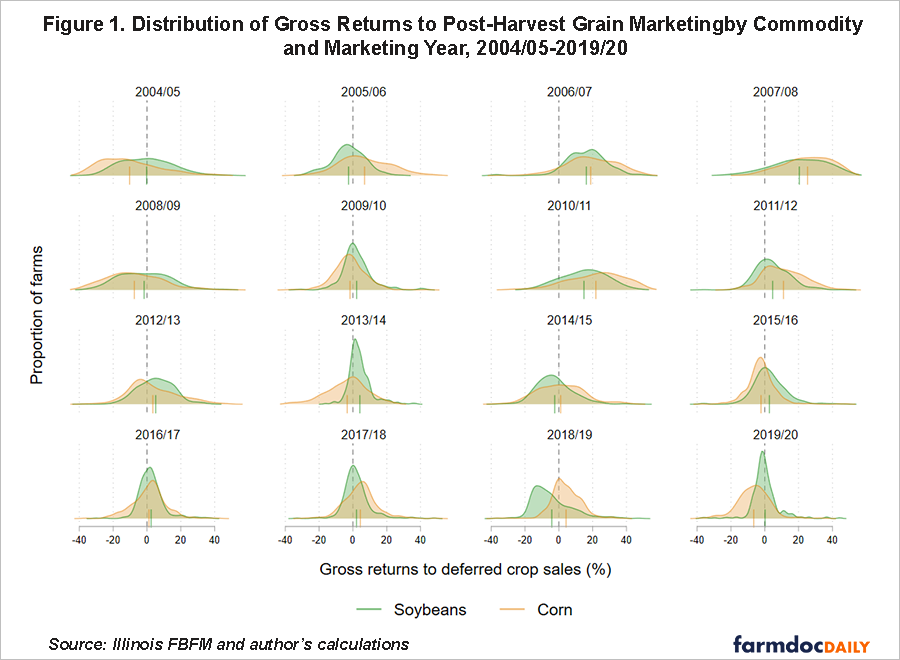

Previous article (daily farm doctor (January 5, 2024), I outlined the distribution of gross profits for marketing post-harvest grain across farms over a 17-year period. Farms, on average, realize gross returns that are roughly in line with seasonal post-harvest price increases, but the range of potential market profits is wide and farms realize negative gross returns. often.

In this article, we unpack this aggregation by comparing year-to-year marketing performance and concurrent intra-year price changes. The range of marketing outcomes is wide, and in any given year some farms perceive marketing losses for their post-harvest grain. The total return to postharvest marketing is correlated with observed seasonal cash price changes. This means that the use of forward contracts is limited, especially in the marketing of post-harvest grain. Note that this analysis ignores the storage costs inherent in marketing postharvest grain, which are important relative to the observed returns. Because storage costs are not zero, the net profit from the postharvest grain market must be lower than the gross profit.

My results suggest that farms should actively consider selling grain before harvest to avoid storage costs and achieve higher average prices. Additionally, farms may be able to utilize forward contract sales for post-harvest delivery to capture post-harvest marketing benefits that reduce price risk. Forward sales are a useful tool in a farm’s price risk management toolbox, both pre-harvest and post-harvest. However, the range of observed results also suggests that it is unrealistic to expect a particular marketing strategy to perform well in all market conditions.

Measuring post-harvest grain marketing benefits

To evaluate marketing performance and assess the extent of marketing benefits, I consider realized selling prices in both the near-harvest and post-harvest periods. Rather than measuring marketing performance against an assumed marketing strategy, such as comparing actual sales prices with observed prices for cash sales at harvest, we measure marketing performance against realized prices for post-harvest sales and for sales close to harvest. Consider realized marketing performance by comparing realized prices. To harvest. Because this comparison is farm-specific, we control for the possible influence of location, marketing skills, and other farm-specific factors that influence marketing performance but do not change over time.

I collected data on annual corn and soybean inventories and production based on approximately 16,000 farm-year observations from FBFM grain farms from 2003 to 2020. Merely observing sales volume and sales value for a calendar year is insufficient to evaluate postharvest marketing performance. The sales price includes the sale of both old crop inventory and new crop production. However, the Illinois FBFM also records the quantities and values of so-called old crop and new crop sales. New production sales are the sales of the current calendar year’s production realized before the end of the calendar year. I call this a near-harvest sale. Close-to-harvest sales are achieved in the sense that deliveries are made before January 1st and profits are earned. Unsold merchandise stored in on-farm warehouses, merchandise delivered to commercial warehouses where title is retained, and merchandise stored anywhere other than prior to shipment. Items for which delivery and transfer of ownership are contracted after January 1st will be considered antique sales for the next calendar year. I call these old crop sales deferred sales.

I measure the total postharvest marketing benefit as a percentage of the difference between deferred and near-harvest sales. This is the total profit excluding costs associated with post-harvest marketing, such as the physical and opportunity costs of holding inventory and interest costs. Accounting for percentage differences allows comparisons between marketing years at different price levels.

Realized profit by release year

We use the distribution of total returns to postharvest grain sales shown in Figure 1 to summarize farmers’ postharvest grain marketing performance. These figures show the percentage of farmers achieving total return levels ranging from -40% to 50% across 16 marketings. Years indicated in the figure. As mentioned in a previous article, the average total return for all years is about 7% for corn and 6% for soybeans. Both the average and range of returns vary by marketing year. The small vertical line in Figure 1 shows the average total profit for each product. These vary from -10 to +25%. In some years the distribution was quite ‘peaked’, suggesting that returns were approximately the same on all farms. In other years, the distribution range is quite wide.

In some marketing years, total revenues are expected to be significantly higher than the long-term average. The marketing years 2006/07, 2007/08 and 2010/11 all had average gross returns of approximately 20%. At the time, many farms were achieving total returns above that level. However, it is instructive to note that even in years when postharvest marketing was highly profitable, a small number of farms realized negative net returns.

Comparison with seasonal price increases

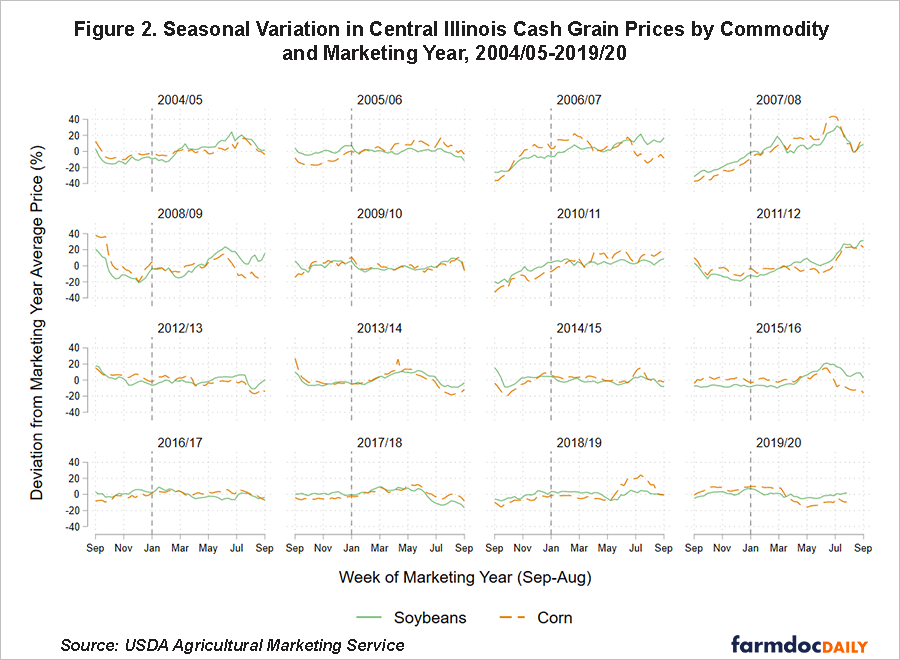

To understand changes over time in the level and extent of total postharvest returns to grain markets across farms, we plot seasonal changes in cash prices for corn and soybeans in central Illinois in Figure 2 . These price levels do not fully describe market conditions, but due to the possibility of futures contracts, the prices available for near-harvest and post-harvest deliveries are a useful estimate of the available prices. It serves as an indicator. In Figure 2, the vertical line in each subfigure indicates his January 1 date that separates the near-harvest and post-harvest periods defined in the FBFM data. Note that if cash prices are high at the beginning of a market year, but are falling (far left of each partial number), this likely indicates that prices were high in the previous market year. This typically indicates higher pre-harvest futures contract prices for delivery at harvest or post-harvest.

Comparing Figures 1 and 2 shows that the greatest success of postharvest marketing occurs in years when cash prices consistently increase throughout the marketing year. Years such as 2006/07, 2007/08 and 2010/11 were years in which cash prices reached seasonal lows at the beginning of the marketing year and reached seasonal highs only by the summer. Post-harvest marketing performance was poor as average spot prices were lower than the previous marketing year, leading to spot prices falling in his September ahead of the main harvest season. Years like 2004/05, 2008/09 and 2014/15.

Although the correspondence between Figures 1 and 2 is not perfect, Illinois grain farms that sell some of their crop after January 1 are correlated with changes in cash prices after January 1. It shows that profits are being realized. This suggests that the farm retains some of its status. – Harvest unpriced grain stocks and infer seasonal cash price increases. If this typical seasonal price increase does not occur, as was the case for soybeans in 2018/19, for example, post-harvest market returns will be very low.

what it means

This analysis suggests that farmers should carefully consider the risk of postponing grain sales, particularly those that are unhedged or otherwise unpriced, until later in the marketing year. Although farmers overall and on average realize benefits from selling later, the mixed outcomes of postponing sales indicate greater downside risk from losses in stored grain. Masu. Farmers manage this risk by actively marketing their grain before harvest and secure profits from post-harvest deferred sales through futures contracts (i.e., selling the “carry” that exists in futures and forward bids). can. However, the correlation between revenue and observed changes in cash prices suggests that many farms carry unpriced inventory after January 1 of each year.

I realize that this analysis benefits from hindsight. All measures of marketing “success” are ex post evaluations of decisions made in the presence of uncertainty about the profitability of various marketing strategies. However, the mixed outcomes observed on these farms indicate that grain marketing is a major challenge for all farms, and farmers should not expect any particular marketing strategy to perform well in all market conditions. suggests.

understand

The authors would like to acknowledge that the data used in this study came from the Illinois Agricultural Business Farm Management (FBFM) Association. Without the Illinois FBFM, such comprehensive and accurate information would not be available for educational purposes. FBFM is a nonprofit organization made up of more than 5,000 farmers and 70 professional field staff and available to all farmers in Illinois. FBFM’s field staff provides farm consultation along with recordkeeping, farm financial management, entity planning, and income tax management. For more information, contact her FBFM office on the University of Illinois College of Agricultural and Consumer Economics campus at 217-333-8346 or visit the FBFM website at www.fbfm.org.

[ad_2]

Source link