In summary

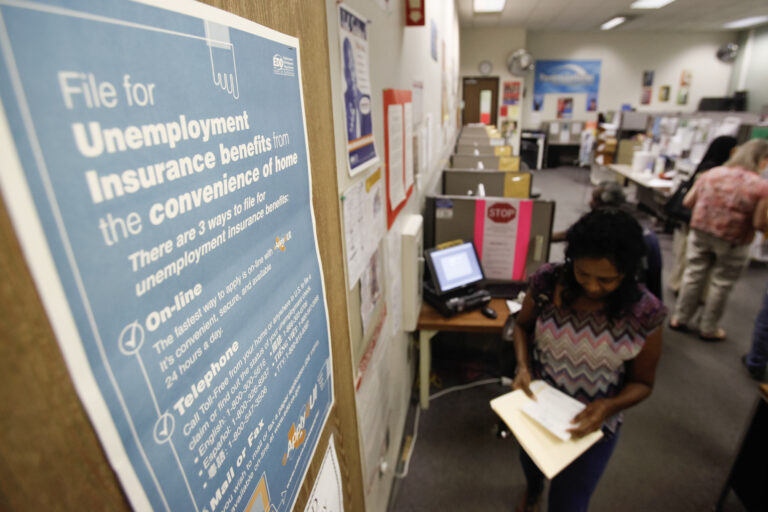

The California Employment Development Department has come under deserved criticism for mismanaging unemployment insurance benefits during the pandemic. There are long-lasting aspects to the meltdown that could cost the state billions of dollars.

One of the most tragic episodes in state government history was the management of the state Employment Development Department, which has left millions of Californians without jobs due to shutdowns ordered by Gov. Gavin Newsom to combat the coronavirus. It’s a bankruptcy.

At the same time, government agencies handed out billions of dollars to fraudsters while failing countless legitimate claims for unemployment insurance benefits. CalMatters reporter Lauren Hepler detailed the devastation last year.

“The year-long CalMatters investigation found that the EDD failed to heed red flags for years, delayed reforms, and abruptly abandoned pre-pandemic efforts to get ahead of an explosion in online fraud.” The issue was rising to the top of the political agenda.” Recession-related agendas and budgets changed in practice as governors, legislators, and federal regulations changed. It was never fixed,” Hepler wrote. “When it all boiled over in the spring of 2020, California experienced the worst of both worlds. Tens of billions of dollars were lost to fraud, workers lost financial security, lost their homes, and extreme In some cases, lives were lost.”

But there is a third element of the EDD catastrophe that still plagues the state and is likely to intensify again if the state’s economy deteriorates. That’s a huge debt to the federal government.

The Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF), supported by employer payroll taxes, is the source of payments to unemployed workers under normal circumstances.

But even in times of relative affluence, the Fund cannot fully absorb benefit claims. The problem stems from two decades of political gridlock that began in 2001, when former Gov. Gray Davis and the Legislature dramatically increased benefits and absorbed most of the $6.5 billion in reserves for the unemployment fund. .

When the Great Recession hit five years later, the UIF quickly ran out of money and EDD borrowed about $10 billion from the federal government to cover increased outflows. Because the state did not repay the loan, the federal government increased payroll taxes on employers to pay down the debt.

Debt from the Great Recession was paid off in 2018, but two years later layoffs caused by the coronavirus hit unemployment funds that were on the verge of depletion. Once again, the state borrowed nearly $18 billion to continue benefits.

In 2022, federal officials raised payroll taxes on employers again (about $21 per worker per year) to offset the fund’s deficit and eliminate debt. The unemployment fund’s debt rose to $20 billion by the end of last year and is expected to reach $21 billion by 2025, according to a new EDD report.

There is a widespread misconception that this debt is due to a surge in unemployment insurance fraud. The fraud is almost entirely related to federally funded extended benefits for workers who are ineligible for state benefits, and has no direct connection to state debt.

Today, even though unemployment rates are relatively low by historical standards, the UIF still struggles to pay benefits. EDD pays out about $6.7 billion in benefits each year, but generates only $5 billion a year in state payroll taxes.

Therefore, the fund is steadily weakening and will no longer be fully able to cope with even a mild economic downturn, forcing states to borrow even more money from the federal government.

This should be a major embarrassment for a state whose governor boasts world-class economic status. But the decades-long stalemate shows no signs of easing.

The union wants to raise taxes to make the UIF healthier, either by widening the taxable wage base by $7,000 a year or by raising the current tax rate of just over 3%. Employers, on the other hand, say they are already paying extra costs to service the debt and want benefits reform.

[ad_2]

Source link