[ad_1]

Mainstreaming gender in smart climate finance is the need of the hour, as SDG financing demands have increased dramatically from US$2.5 trillion to a staggering US$4 trillion. Although the debate on climate finance has been active over the past few decades, it is only recently that gender perspectives have been incorporated into the climate debate. Although there is no fixed definition, gender-smart climate finance aims to incorporate a gender perspective into climate-related financial investments, policies and programs. Climate change initiatives here recognize the disparate impacts of climate change on women and men, leverage women’s unique skills/experiences, promote gender equality, and drive change to empower women in the long term. I aim to make it happen. This approach maximizes the effectiveness and sustainability of climate action by considering gender-specific vulnerabilities and strengthening women’s resilience.

Although there is no fixed definition, gender-smart climate finance aims to incorporate a gender perspective into climate-related financial investments, policies and programs.

The Indo-Pacific region, prone to climate change-induced disasters and widening gender disparities, is marred by multiple challenges. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), women spend four times as much time as men in unpaid care work, the highest figure globally, and in this region, only women are employed. This is only 43.6% of men, compared to 73.4% of men. These gender disparities hinder women’s involvement in climate finance and, in turn, hinder efforts to tackle climate change. This is also underlined by the region’s limited representation of women in decision-making in environment ministries, with fewer such ministries headed by female ministers, compared to a global average of 12%. is only 7%.

Climate change as a “threat multiplier” exacerbates existing socio-economic inequalities for women and creative communities. This is because their livelihoods are highly dependent on natural resources, and they participate in activities such as agriculture and fishing, both paid and unpaid, and are further burdened with the primary task of ensuring food security. has been done. These are further exposed to difficulties during periods of drought and unpredictable rainfall, impacting their ability to sustain continued contributions in these areas. From 2010 to 2021, more than 225 million people were displaced by natural disasters in the Indo-Pacific region, and these disasters disproportionately affected women and had higher mortality rates compared to men. is shown in the survey results. Additionally, displacement due to natural disasters leads to increased rates of gender-based violence, with women in the Indo-Pacific region experiencing gender-based violence at higher rates than the global average.

From 2010 to 2021, more than 225 million people were displaced by natural disasters in the Indo-Pacific region, and these disasters disproportionately affected women and had higher mortality rates compared to men. is shown in the survey results.

Current status of gender finance in climate change countermeasures

Given this dark reality, only 0.01 percent of global funding actually supports projects that address both climate change and women’s rights. From 2021 to 2022, the average annual flow of climate finance increased by about $1.3 trillion, but the funds are either going to traditionally male-dominated sectors or are too weak to proactively address the gender gap. Not yet reached.

However, climate change initiatives such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which are at the forefront of climate finance, are taking a gender-sensitive approach to resource allocation decisions. Along these lines, the United Nations adopted the Sendai Framework, which calls for the inclusion of gender mainstreaming in disaster risk reduction (DRR). These provide a framework within which gender considerations can be mainstreamed in climate finance.

At the forefront of climate finance, climate initiatives such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) are taking a gender-sensitive approach to resource allocation decisions.

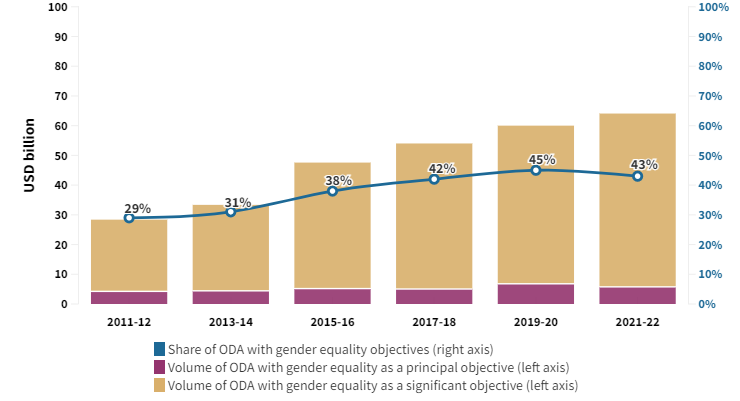

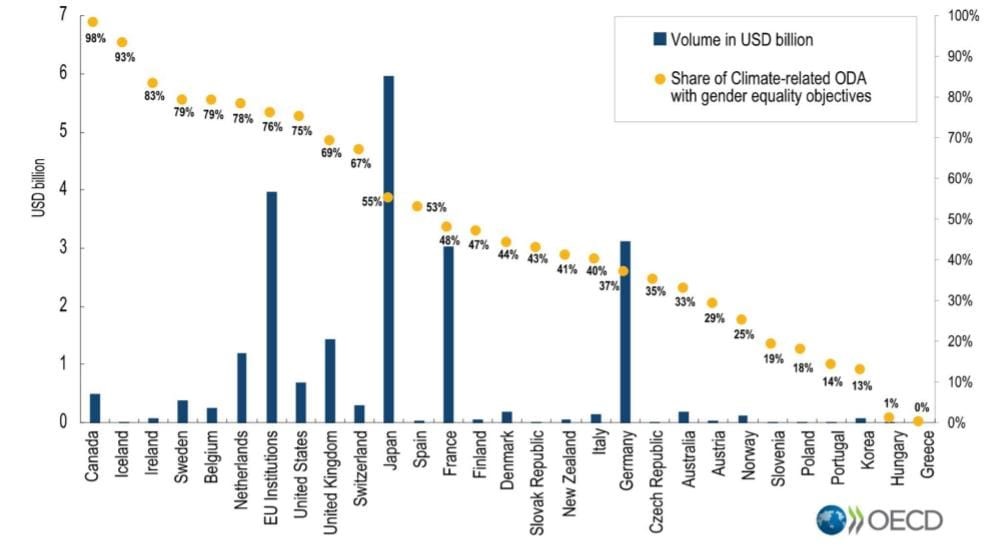

In 2021-2022, 43% of bilaterally distributable ODA prioritized gender equality as a policy objective, amounting to USD 64.1 billion, down from 45% in the previous year (Figure 1). Of this, only 4% went to programs with gender equality as their main objective, and 1% of total bilateral ODA (563 million yen) was allocated to combating gender-based violence. US dollar). This allocation raises concerns about the limited focus on gender inequality while addressing climate change. Figure 2 shows the country distribution of climate-related ODA with gender targets.

Figure 1: Distributable ODA with gender equality as a policy objective (2011-2020)

sauce: OECD, 2022

Figure 2: Percentage of OECD donors incorporating gender equality in climate-related ODA

sauce: OECD, 2022

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has prioritized gender equality, with 68 percent of its Climate Investment Fund (CIF) projects incorporating gender considerations and increasing women’s participation in climate change projects across the Indo-Pacific region. is given priority. Six gender-mainstream CIF projects have been implemented in the region, but these projects are still in their infancy, making it difficult to assess their effectiveness.

There is also an inherent bias in climate finance when it comes to adaptation versus mitigation. According to the Adaptation Gap Report 2023, developing countries’ adaptation financing needs are up to 18 times greater than current public funding flows from developed countries. Despite 38 per cent of adaptation funding being allocated to gender equality, there is a clear lack of prioritization as a ‘main purpose’.

Additionally, several actors in the region, including the United States, France, Japan, Australia, the United Kingdom, and India, have demonstrated a commitment to mainstreaming women’s voices and promoting gender interventions on climate change. For example, the United States has been working with Pacific Islands under the Pacific Energy and Gender Strategic Action Plan (PEGSAP). She aims to provide US$1.5 million to advance women’s leadership in clean energy. This includes pilot projects for women-owned renewable energy businesses and STEM scholarships for women and girls in 22 Pacific Island countries and territories. Additionally, the Indo-Pacific Triangular Cooperation (IPTDC) Fund, led by India and France, is an important step under the Horizon 2047 roadmap. The fund is SDG-focused and aims to target climate change, with SDG 5 a priority. India’s engagement with Germany under the triangular formula of development cooperation is also important. Promoting agribusiness among Malawian women is a suitable project under this initiative.

India’s involvement with Germany under the triangular scheme of development cooperation is also important.

Similarly, in the Australian Government’s grants for gender equality and climate change in the Indo-Pacific region, climate finance targets climate adaptation and mitigation from a gender perspective. As part of the Indo-Pacific Strategy, the UK has launched a Work in Freedom (WIF) program to protect female migrant workers from human trafficking and to build women’s resilience and promote women’s leadership through grassroots women’s organizing. launched the Climate Resilience Partnership Program (CRPP). Japan’s revised ODA Charter focuses on gender mainstreaming at all stages of development cooperation, including in areas such as climate, food security and education.

Inclusion and quality financing in the Indo-Pacific region

It is essential for the Indo-Pacific region to take a contextually inclusive perspective to address the intersectionality of gender and climate. The Indo-Pacific region hosts 84% of all Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects registered under the Kyoto Protocol of the United Nations Climate Change Convention, but only a handful of countries utilize them effectively. It is. While China and India are the largest recipients of global climate finance, the region’s most vulnerable countries, such as Pacific Island Countries (PICs), receive the least amount of funding. Additionally, many Clean Development Mechanism projects have been found to ignore smaller-scale initiatives that involve and benefit women.

While China and India are the largest recipients of global climate finance, the region’s most vulnerable countries, such as Pacific Island Countries (PICs), receive the least amount of funding.

Addressing climate change in the Indo-Pacific region requires US$1.1 trillion a year, while closing the gender gap could inject US$3.2 trillion into the region’s economy. Therefore, integrating climate financing with gender-specific approaches provides a strategic means to tackle climate issues and promote socio-economic growth, aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals and ensuring smart climate financing. represents the paradigm.

Indeed, there is both a “great need and a great opportunity” to deepen investment in gender-smart climate finance. For climate change financing to be truly “smart”, it must incorporate a gender perspective. Failure to take gender into account in climate action increases the risk that broader sustainability challenges will not be effectively addressed.

A people-centred approach that recognizes the actual grassroots needs of communities and women is key. However, challenges remain due to a lack of gender-disaggregated data and a lack of private sector engagement, with only 4% of global private assets currently going to developing economies. I am. It is therefore essential to adopt a gender-transformative approach and foster effective cooperation between state and non-state institutions. Several opportunities exist for the Indo-Pacific region that could help unlock the true potential of climate finance to build a more just and resilient future for all.

Swati Prabhu He is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation’s Center for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED).

sharon sarah tawaney I am the assistant director of the Observer Research Foundation.

The above views belong to the author. ORF research and analysis is now available on Telegram. Click here to access our carefully selected content (blogs, long-form articles, interviews).

[ad_2]

Source link