[ad_1]

Back in 2018, Denver voters approved a new way to campaign for City Hall.

The Fair Elections Fund (FEF) aimed to address two issues simultaneously. One is to reduce the power that outside money can use in elections, and the other is to increase the chances that rough-and-tumble candidates have a fighting chance.

Candidates who chose to participate in the fund could receive only small donations from individuals and no contributions from corporations or political action committees. But these small donations earned a 9-1 match from taxpayer coffers, meaning ordinary residents could be more powerful than ever in shaping local races. .

This week, Denver Clerk and Recorder Paul Lopez released a post-mortem into the program’s initial implementation during the 2023 mayoral and city council elections. He has one important point. That is, people used up the cash they earned in the program.

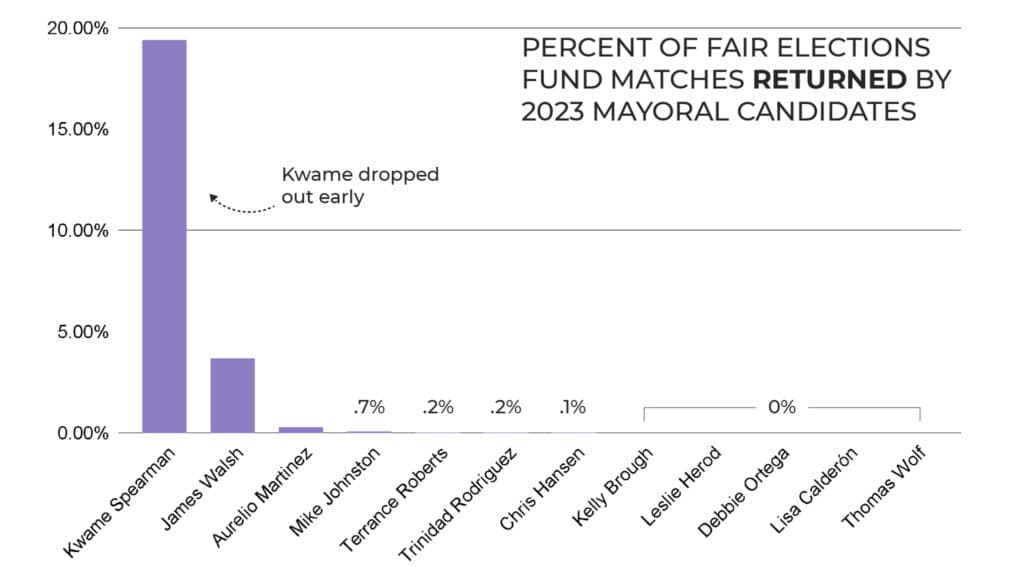

Just under 3% of games were unplayed.

FEF rules state that candidates must return unused matches once the election is over and the dust has settled. Most people who used the fund in 2023 used up almost every dollar they received from the city pool, according to Lopez’s report.

Of the candidates who chose to participate in the fund, 19 out of 46 of all races returned their zilch to the city, meaning they spent every last dime. In addition, he had to repay 10 people less than $100.

Nine candidates returned more than $1,000, most notably incumbent City Council members Paul Cushman and Stacey Gilmore, who joined the fund despite running unopposed. Both spent zero on the match and returned his 100% of the FEF pool to the program.

Most others spent at least 95% of the match. Example: Flor Alvidres, who won the District 7 seat, returned his $6,600, which is 5% of the amount he received. Mike Johnston, who won the mayoral race, gave back about $500, or 0.7 percent of the match. Shannon Hoffman returned $1.51 of the $142,000 she received and ultimately won against incumbent Chris Hynes in District 10.

Data Source: Denver Elections Division

In total, 45 FEF candidates raised more than $7 million in matches and returned just over $200,000. That’s 2.8 percent. (Check out the dataset here.)

Both mayoral candidate Ean Thomas Tafoya and Ward 9 candidate Kwon Atlas are said to still owe some of that money back. The city said Atlas had repaid the money. They say Tafoya is missing about $600. He said this was due to a missing receipt and is working with the Denver Department of Elections to resolve it.

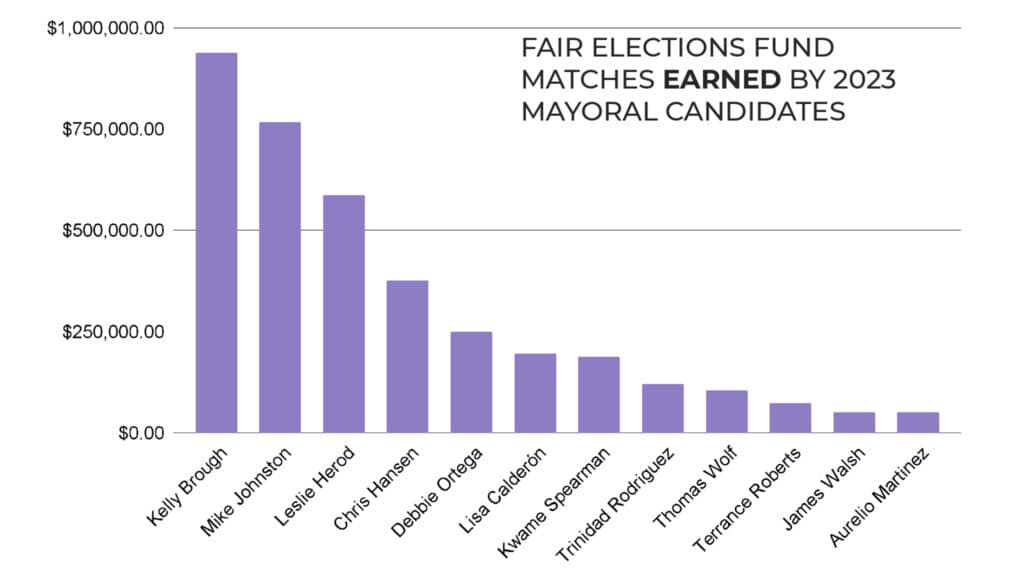

That’s a lot of money to fund a largely unsuccessful campaign.

While most candidates chose to join the Fair Elections Fund, mayoral candidate Andy Rujo made opposition to the Fund part of his campaign. On the campaign trail, he said the city shouldn’t subsidize elections and said the foundation was “throwing money” at political issues instead of real ones. Mr. Lujo self-financed his campaign, but quickly lost out to his opponent, who took part in a city-based race.

But some candidates who benefited from the fund said the city could reform how it funds the program.

Mayoral candidate Lisa Calderon, who has given Johnston a “report card” rating since he won the race, said the new FEF qualification, which could factor in outside funding, has given Johnston a “report card” rating since he won the race. He said he would like to see an upper limit set.

Another section of Mr. López’s report focuses on these resources, namely independent expenditure committees that lined their own pockets and supported candidates (they are also not supposed to have contact with candidates). ). Mayor Johnston received approximately $3 million from three outside donors: former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, and former DaVita CEO Kent Tilley.

“I would love to participate in the reconfiguration meeting to discuss the necessary adjustments.” [to the FEF]So it doesn’t tend to favor wealthy candidates as much,” Calderon said.

A spokesperson for Mr. Johnston’s campaign told The Denverite last year that the independent spending committee operates separately and that these big donors are working on “tough issues like addressing homelessness and housing affordability.” “I’m excited about Denver’s potential as a proving ground for the nation as we address this issue.”

Debbie Ortega, a former City Council member who also ran for mayor, said the same thing.

“The real issue is that dark money continues to play a significant role in these campaigns,” she said.

She added that she was concerned that the cash would end up going to candidates who won’t even be on the ballot. Mikayla Ortega, a Denver elections spokeswoman, said that while that didn’t happen this time, it’s still a good idea to have guardrails.

Data Source: Denver Elections Division

Both former candidates said the fund may also undergo some streamlining because fiscal and reporting requirements are difficult to accommodate.

“I had to have two separate bank accounts,” Ortega said, adding that it took a lot of effort and guidance to use the FEF money correctly. “The process turned out to be the stupidest thing I’ve ever been through.”

Although there may be room for improvement, Lopez calls 2023 a success.

“The Fair Elections Fund has undoubtedly reshaped Denver’s electoral landscape, achieving its goals and serving as a beacon of transparency, accountability, and continuous improvement in the realm of local democracy,” said Secretary. is written in the report.

He noted that compared to the 2019 and 2015 Denver mayoral elections, the average donation amount in 2023 has decreased from about $300 per donation to $100 per donation.

“This marked a significant shift in campaign finance in favor of giving small donors a voice,” the report states.

It also touts the increase in the number of individual donors to these elections from 25,000 in 2019 to more than 50,000 in 2023 as a sign of “increased engagement.”

(Incidentally, Mr. Lopez, who ran unopposed, returned $0.29 of the $62,000 he received from the fund.)

Still, 2023 was the most expensive election in the city’s history. Between FEF funds and independent spending committees, candidates spent nearly twice as much in 2023 as they did in 2019.

Calderon and Ortega said they still have some concerns about the system, but said the money was mostly well spent. Neither of us knew we would have made it this far without it. It’s worth mentioning that Calderon almost advanced to the mayoral runoff.

“It was absolutely worth it, because we were able to pay our workers more than a living wage, and we worked on a very competitive, very compressed schedule and cut-throat race. And we were able to reward that work. We couldn’t have done it otherwise,” she said. “I would rather have that kind of system than a wealthy candidate backed by a billionaire.”

[ad_2]

Source link