[ad_1]

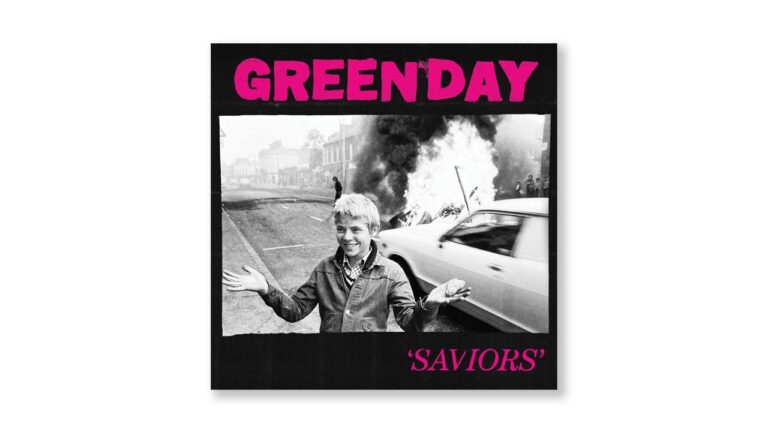

From a distance, Green Day doesn’t seem all that difficult to understand. For decades, the band has reliably churned out chunky three-chord earworms about jerking off, boredom, growing up, wasting money, and resisting “subliminal mindfucks.” But its remarkable endurance, combined with its long tail of influence, suggests something deeper. Last week, Green Day released their 14th album, Saviors. The band’s lineup (singer/guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong, bassist Mike Dirnt, and drummer Tre Cool, now 51) has remained unchanged since 1990. A story of adult hypocrisy and an examination of adolescent neuroses, it’s a relentlessly dynamic work that makes it nearly impossible for a die-hard to sit still during its performance. Produced by hitmaker Rob Cavallo, the album feels like a distillation of Green Day’s decades-long mission to point out that modern life is mostly shitty.

But perhaps what’s most compelling about “Saviors” is how modern it feels, and it’s not because Green Day bowed to the whims of the zeitgeist, but because somehow This is because the zeitgeist has bent around Green Day. The brash, propulsive pop-punk that the band engineered and perfected in the mid-’90s is now everywhere. Last year’s hit “Get Him Back!” by Olivia Rodrigo drew instant comparisons to Avril Lavigne, a professed disciple and follower of Green Day. When Billie Eilish was given the task of introducing Green Day at the American Music Awards in 2019, she was serious, almost serious. “No band was more important to me and my brother when we were growing up.” she said.

Of course, Green Day didn’t invent pop punk. The Clash had a hook for days. Look at the brevity and vigor of the Ramones or the Buzzcocks. Or go even further back and add a few layers of distortion and feedback to the Beatles’ 1965 “Help!” and the seeds are there (tuned urgency, gentle self) -disgust, people in their early 20s (a sense of premature nostalgia that often strikes). But by tweaking and popularizing the form for a new era, we’ve inadvertently established its signifiers: (very) low-slung guitars, smudged black eyeliner, and infinite fucking energy. was Green Day. I think the band’s dynamism is due to two central tensions. Armstrong is gentle but sarcastic, sometimes swinging from confession to accusation in a single verse. Similarly, his band’s best songs are bodied, visceral, almost carnal, but not without surprisingly elaborate narratives. (Green Day has released two of his rock operas: 2004’s smash hit “American Idiot,” which was later a successful Broadway musical, and 2009’s sprawling sequel “21st Century ) Every song feels like a tug-of-war. The war between the brain and the body, sadness and joy.

Still, in the early ’90s, Green Day received some recognition as one of the first to officially add “pop” to a genre that, at least in theory, was philosophically at odds with fame, idolization, success, and money. was criticized. . At the time, even the term “pop punk” seemed like an oxymoron, a joke, an instant pejorative. Dookie, the band’s groundbreaking third album and first on a major label, was released when I was only 14, which is probably the best age to receive it (gentle, I was excited and bored). I recently got pink streaks in my hair using a tub of contraband Manic Panic, and I can’t lie awake at night wondering how angry my parents will be if Piercing Pagoda shoots a tiny barbell between my eyebrows. It happened often. One of my best friends was two years older. He had a driver’s license and occasionally used his father’s khaki two-door Honda Accord. That winter, we listened to “Dookie” on a dubbing cassette and shouted along to “Basket Case” while sticking our heads out of the sunroof and manually rolling down the windows. paranoia? Or am I just stoned? ” (or, as Armstrong says in his second chorus, “Am I just paranoid? Huh, no, no?”)

But there was squint-eyed chatter among the arm-in-arm set, all the irritated older brothers and record store clerks in our town, and Green Day was sold out. They gave up independent Lookout! Records, home of Operation Ivy, Screeching Weasel, and The Mr. T Experience, has signed Reprise. In 2024, it’s hard to understand how grave an insult this is. In the ’90s, sacrificing your creativity in exchange for airplay on MTV or commercial radio was devastatingly lame. Green Day formed in Berkeley in his late ’80s, a gritty, independent, all-ages punk club at 924 Gilman Street that was a staple of the scene. (The band’s first name, Sweet Children, is still spray-painted on the ceiling beams.) “Green Day” itself was slang for getting high. Armstrong dropped out of high school and hung out in various punk warehouses around the East Bay until the band got off the ground. Who did Green Day think they were? Bon Jovi? But in the end, “Dookie” was raw, improvisational, funny, loud, nervous, raw enough to earn the band some kind of forgiveness. (“Dookie” eventually sold more than 10 million albums for him in the U.S. alone. Let them eat.)

Along the way, the band became increasingly political. “American Idiot” tackles the warmongering of the post-9/11 Bush administration with real venom, and the new song “Coma City” is also an angry appeal to gun control and billionaires with no moral values. is being strictly pursued. “Bankrupt the Earth,” Armstrong sings, “for the bastards of the universe.” (Armstrong’s vocals here are a little reminiscent of Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros’ perfect “Coma Girl” from 2003.) Late last year, Green Day released “Dick Clark’s New Year’s”. When he appeared on “Rockin’ Eve with Ryan Seacrest,” it caused a huge uproar. He created a mild smear by replacing the lyrics of the title song of “American Idiot,” changing “I’m not part of the redneck agenda” to “I’m not one of the rednecks.” Maga agenda. “That’s fucking Hitler,” Armstrong, an ardent and consistent supporter of Democratic candidates including Bernie Sanders, said in 2016 when asked about Donald Trump. After the election, he shouted, “No Trump, no KKK, no fascist USA!” At a TV awards ceremony. That’s why we see pictures of crowds of very happy, clean-cut young people gathered in Los Angeles television studios, bouncing along to scathing songs about cultural and political ignorance. It still gives me a wild feeling. Armstrong sings on the new album: “We are all together, living in the 20’s. . . . My condolences.”

One of the best tracks on Savers, “Susie Chapstick” is a sad-eyed, nervous, sweet lament for wasted bonds in the spirit of Big Star. Armstrong sounds wistful, thinking about one of the relationships we might have in another life. “Have we overcome our innocence? Have we taken the time to make amends?” he sings. Loneliness, or solitude, is felt in Armstrong’s choruses, from “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” (“Only my shadow walks next to me”) to “Brain Stew” (“Alone, here I go”). It’s a recurring theme. To “Walking Alone” (sometimes I still feel like I’m walking alone). Armstrong also writes often about feeling insane, which is only exacerbated by the confusion and cognitive dissonance of the 21st century. In the album’s final song, “Fancy Sauce,” Armstrong sighs at the evening news and says, “This is my favorite cartoon.”

“Saviors” ends amidst the faint sounds of raucous guitars and drums. It feels amazing that Green Day found a way to retain that energy, that young, salty sense of righteousness and courage so deep into the band’s career. It’s great to see those lessons being passed on to a new generation of punk, pop punk, or whatever you want to call it. “We all die young at some point,” Armstrong exclaims. In fact, the “Savior” gives rise to the idea of eternal youth, the preservation of everything, spiritual and everything. Elan Vital It gets your heart beating, it primes you for action, it keeps you open to despair, victory, rage, and whatever else may come your way, making you feel infinitely beautiful and capable. ♦

[ad_2]

Source link