[ad_1]

About a month ago, I co-authored an article for The Crimson about anti-Semitism at Harvard University. Since October 7, another story has been unfolding alongside the anti-Semitism on Harvard’s campus: the story of the public’s response to it. This work is about that story.

My brother Caleb is currently taking a gap year in Israel, just as I did over two years ago. In the weeks following the October 7th massacre, my mother told me about several conversations she had with her friends.

Her friends often asked her, “What’s Caleb doing these days?” Then, their eyes widened with concern, they asked: “So, what about Isaac?” I hear it’s really bad over there…” It was as if I had vacationed in a bomb shelter. As if I were living in a war zone.

For several weeks after October 7th, I felt like I was in a strange world. People were more concerned about the provocative, thoughtless, and reprehensible statements made by several loosely affiliated Harvard clubs than they were about the real-world events they described.

My home country, Canada, broke away from its pattern of voting in favor of Israel at the United Nations, a change that is hardly talked about by comparison.

The media seemed strangely willing to interview my people at a time when the people of Israel and Gaza were suffering on a daily basis.

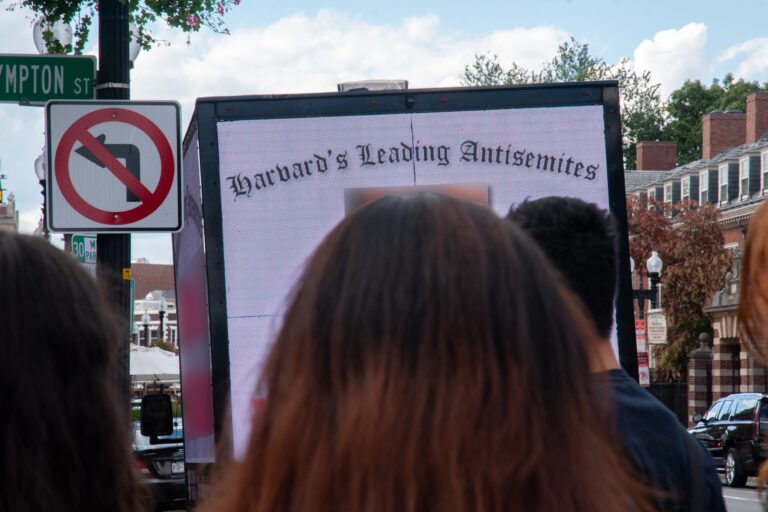

The group went so far as to create ridiculous planes with similarly ridiculous messages about Harvard University’s anti-Semitism problem, and to blind passersby by flashing the names of students even remotely connected to their statements. I felt it was necessary to waste time and money by outsourcing personal information collection trucks. , while causing great damage to those targeted.

The impact of the Harvard crisis reverberated throughout the upper echelons of American political society. As the U.S. government adjusts policy in two foreign wars and grapples with severe political instability and record low approval ratings, mainstream media and politicians remain focused on university discourse.

In 2006, Congresswoman Elise M. Stefanik (considered a Jewish hero in the fight against anti-Semitism on college campuses) praised Hitler (and later apologized) and continued to support Trump after becoming president. He actively campaigned in 2021 with the aim of becoming a parliamentary candidate who will support him unwaveringly. 2022 dinner with Kanye West and Nicholas J. Fuentes, who are widely known for their anti-Semitic rhetoric. Despite his connections to these figures, Stefanik capitalized on the Harvard debacle and shot to national attention.

At times, I felt like a political football.

Nevertheless, former university president Claudine Gay repeatedly failed to answer Stefanik’s questions and categorically stated that she called for genocide against Jewish students, even if legally justified. is a violation of Harvard University’s Code of Conduct and appears to be shameful, deeply hurtful, and inconsistent with University rules. Commitment to combating prejudice.

While some celebrated Gaye’s resignation, believing that anti-Semitism had somehow been vanquished, at a time when leadership and vision were sorely needed, we also had no clear path forward and no institutions. There were no concrete initiatives for reform. For those who claim victory, I believe this is at best a pyrrhic victory, one that will long fester as an open wound on our campus.

Over the past few months, my faith in Harvard has been eroded by a wave of indecision, gross mismanagement, and mixed statements that somehow seem to be about me but never about me. I was shaken to the core.

That Harvard University appears to be willing to spend nearly unlimited resources on repeated attempts to rehabilitate its own image rather than on sincere efforts to understand my community and others. I will continue to be frustrated.

It will continue to be difficult to view some of my classmates the same way when I see posts denying rape or justifying murder. Because it’s politically easier than accepting complex truths.

And I will continue to be extremely anxious when I hear the chant, “Globalize the Intifada,” on my way to class.

But that’s just it. I’m heading to class.

I go to class, eat dinner, do some work, and then go to bed. After all, I’m still a college student. Because on this campus, we are still college students.

Over three months ago, I spoke with a Harvard graduate whose son is serving in the Israel Defense Forces. Much of his son’s unit was killed on October 7th – his son was thankfully off base for the Sukkot holiday – and he wanted to hear an update from his alma mater.

I didn’t know what to say to him other than to tell him not to worry. At the time of our conversation, thousands had been killed and hundreds still held captive. Much of the space on both sides of the Green Line was still unfilled.

I think the group that made the first statement that brought public attention to Harvard knew very well that it would attract significant media attention. Generally speaking, that is the sole purpose of public statements. The media apparatus, ostensibly stunned and outraged, escalated this statement into the stratosphere. The aftermath sparked a conflagration that, if anything, dramatically increased polarization, fear, and hostility, enraging everyone for one reason or another.

Very few people live a better life because of it.

Now, one of the first things I do every morning is look into the faces of those killed overnight and pray I don’t recognize any of them. I think many Palestinians are the same way.

Suddenly, what’s happening at Harvard doesn’t seem so pressing.

Isaac R. Mansell ’26, Crimson Editor, is a statistics concentrator at Kirkland House.

[ad_2]

Source link