[ad_1]

Last year, film critics took to each other to praise Oppenheimer, the Hollywood blockbuster against Robert Oppenheimer, known as the father of the atomic bomb.

The New York Times hailed the biopic as “a drama about individual and collective genius, hubris, and fallacy.” [that] This is a brilliant depiction of the eventful life of an American theoretical physicist who contributed to the research and development of the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. This catastrophe ushered in the era of human domination. ”

Oppenheimer, who is widely expected to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, portrays his eponymous protagonist as a complex but heroic figure who, oddly enough, later denounces the proliferation of nuclear warheads only to denounce the hydrogen bomb. He is the person who created (H-bomb). He did not express any remorse in his public life for the Japanese casualties caused by his invention.

And while the film goes to great lengths to explore Oppenheimer’s inner turmoil, scenes of the hellish fires on the ground in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are nowhere to be found in this three-hour epic. Not found.

Oppenheimer’s solipsism is representative of the Hollywood film industry, which is both a maverick and a trendsetter in world cinema, said Tukufu Zuberi, chair of the sociology department and professor of Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania. .

“Oppenheimer gives us the idea that something sublime was going on in the making of the atomic bomb,” Zuberi told Al Jazeera. “But that wasn’t the case. We didn’t need a bomb to end the war. The Japanese army had already surrendered. We were going to show the world, primarily the Soviet Union, what happens when you fight America. We bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki for this purpose.”

Zuberi said the expressions of shock and awe at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were “at the heart of NATO’s mission and the military-industrial complex on which the United States relies to do business with the world.” “Well, welcome to 2024. There are an incredible number of wars going on, and they all depend on certain stories about the past, and if we don’t tell stories that make people feel okay about it, It won’t.

“The last thing I want to see is a movie that claims that the military-industrial complex has introduced a new process of settler colonialism based on white supremacy.”

“The most important thing in art”

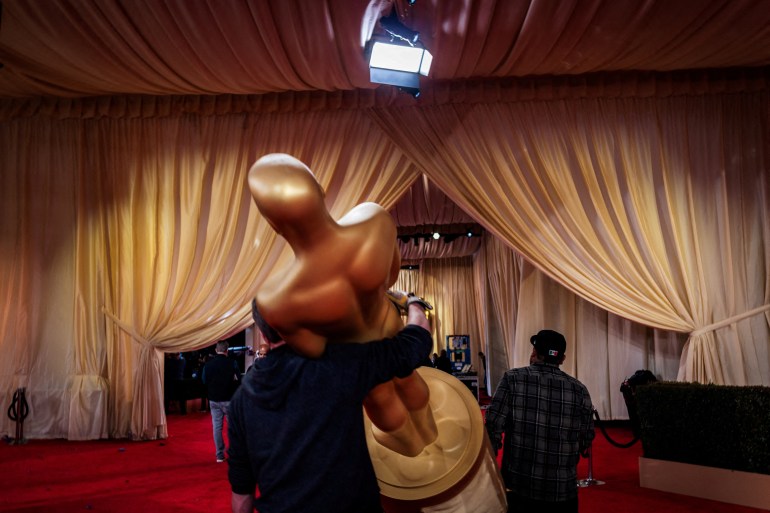

Sunday night’s Academy Awards ceremony is marquise night for the Hollywood film industry. But while movies may be America’s greatest cultural export, their international reputation has been tarnished by a tendency to romanticize, if not completely ignore, the West’s dispossession of much of the world, especially the Global South. Several film scholars told Al Jazeera. This is because the main purpose of Hollywood movies is to entertain people, not to raise consciousness, promote social change, or challenge class relations. For example, Italian director Giro Pontecorvo’s 1966 classic “The Battle of Algiers” and Senegalese director Ousmane Sembene’s “Black Girl” were released. and his 2011 masterpiece A Separation by Asghar Fakhradi, to name just a few.

“Hollywood, by and large, is not set up to make revolutionary films,” said Nana Acheampong, director of the Department of Creative Arts at Africa University in Accra, Ghana. “They are driven to make films that will soothe, console, and make people feel good.”

Film historians generally attribute the world’s diverse film output to the political tensions that defined the 20th century: capitalism versus communism. Vladimir Lenin declared that “for us cinema is the most important of the arts,” and he used Soviet cinema to form a national identity and unite the Russian tribes, which had historically been at odds with each other. Nationalized industry. As a result, Russian writer Sergei Eisenstein’s films, particularly Battleship Potemkin and Strike, were heavily influenced by Eisenstein’s rival director D.W. This is in stark contrast to racist Hollywood movies like “Birth.”

From its early days, cinema developed along two distinct trajectories, with much of the world parroting Italy’s gritty post-war neorealism, while Hollywood sought to protect the nation by glorifying the individual rather than the community. It went its own way with a romantic script aimed at numbing revolutionary impulses. And he encourages obedience to authority.

Keeping the lie of white settler colonialism alive

Zuberi said the 2023 blockbuster “Killers of the Flower Moon” is a good example. The film, directed by Martin Scorsese and nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture, stars a corrupt local, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, who is accused of stealing oil-rich land from an oil-rich Native American tribe in Oklahoma in the 1920s. The film depicts a political boss facing criminal charges.

“While this is presented as some kind of exceptional activity, it was actually a U.S. policy to steal land from indigenous peoples,” Zuberi said. “Very few people went to prison.”

From Brazil to India’s Bollywood, Mexico to Turkey, Argentina to Nigeria, the film industry has taken off as more countries seek to understand their colonial past and its aftermath. In comparison to these recent works, Africans see typical Hollywood films in terms like those used to describe cartoons, such as funny but mediocre, or laugh-inducing but ultimately unsatisfying larks. It’s not uncommon to hear it explained. However, Zuberi argues that it is difficult to describe Hollywood films as Orientalist (a term coined by Palestine scholar Edward Said to describe Western efforts to justify colonialism through artistic misrepresentation). Said it’s not completely accurate. This is because most studio executives in the United States are painfully ignorant of the historical consensus. .

Adisa Alkebran, a film scholar and professor of African studies at San Diego State University, told Al Jazeera: [Hollywood executives] They’re just looking for interesting stories that they think their audience will respond to, not necessarily stories that have the potential to raise awareness among a particular group of people. ”

Ever since 29 African and Asian countries came together in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955, the African film industry has primarily sought to portray Africa’s struggle for independence in intimate and innovative ways. As an example, Zuberi points to the 1973 Senegalese film Touki Bouki, which, to put it too narrowly, is Ferris Bueller’s Day Off in an anti-colonial context.

However, both Zuberi and Acheampong point out that the global film industry is moving towards the blockbuster style pioneered by Hollywood and reaping financial benefits. More and more African films are following the romantic comedy formula popularized by Hollywood and featuring exceptional black protagonists murdering their enemies one after another, each bloodier killing than the last.

“The main role is [Hollywood] The purpose is to make money,” Todd Stephen Burroughs, author and adjunct professor of African studies at Seton Hall University, told Al Jazeera. “But while making money, we import values and brutal manipulations of sound, text, speech, etc., knowing the effect it has on the nervous system. But this is because all art is propaganda. It’s even more complicated than that, and I don’t agree with that. As an individual who consumes media, I consume and enjoy these things, but how does that affect me psychologically? Most people in America and around the world are anti-intellectual. Most people have never studied what the role of the media is.”

Mr Zuberi said: “If you look at what’s happening in Gaza right now, you can clearly see that Hollywood movie narratives are full of justifications for the state of Israel.

“The reality is that a large part of Hollywood is just keeping the lies of white settler colonialism alive.”

[ad_2]

Source link