[ad_1]

USC’s Office of the Executive Vice President for Health Affairs awarded the university’s first NEMO awards to two teams of USC researchers from the University Park campus and the Health Sciences campus.

The NEMO Prize is the result of a generous gift from Sherry and Ofer Nemirovsky. After University of Pennsylvania School of Business and Engineering alum Ofer Nemirovsky started the award at his alma mater, the couple looked for an opportunity to do the same at the University of Southern California. Sherry Nemirovsky graduated from the university in 1985 and currently serves on the university’s board of trustees. as a member of the President’s Leadership Council;

Sherry Nemirovsky said, “It’s really life-affirming to me to see what happens when the right brains get together in the right room.” “The concept of combining engineering and medical schools and what they accomplish is just amazing.”

The highly selective $125,000 prize winners, to be awarded to two teams each year for the next five years, will help bridge the gap between ideas and clinical breakthroughs in health and engineering collaborations. We proposed a project designed to. This award aligns with Chancellor Carol Folt’s Health Sciences Transformation “Moonshot” to leverage USC’s research, medical training, and clinical care to innovate and better serve patients and communities.

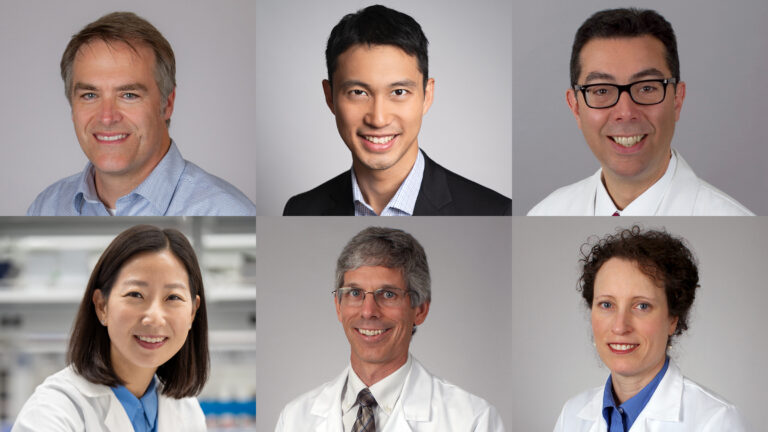

One of the winning projects, “RNA-based nanoparticle therapy for polycystic kidney disease,” was co-authored by Ken Hallows, professor at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, and Nuria Pastor, director and co-director of the USC Polycystic Kidney Division. Includes Associate Professor Soler. The Keck Medicine clinic at USC is a collaboration with Associate Professor Eun Ji Chung and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering’s Dr. Karl Jacob Jr. and Karl Jacob III Early Career Chair. The trio aims to perfect a treatment that targets the root cause of polycystic kidney disease before patients require dialysis or kidney transplants.

The second group of winners includes Professor Wade Hsu of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Professors Brian E. Applegate and John S. Ogarai, Professors of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery and Biomedical Engineering. and is participating in a project titled “Transmission optical tomography of the human cochlea.” The prize money will go toward developing ways to image the inner ear to address issues related to hearing loss and vertigo.

“These awards recognize the power of collaboration between engineering and health sciences and how researchers from different schools can strengthen their individual strengths by combining their skills, expertise, and dedication to scientific discovery. “This is an exciting reflection of the United States,” said Stephen D. Shapiro, USC’s senior vice president. President in charge of health. “Together, we are stronger as we continue our mission to provide life-saving care and research.”

Target the root cause of disease

Dr Hallows describes polycystic kidney disease (PKD) as one of the most common and potentially fatal genetic diseases across all backgrounds. According to the research team, about half of people with PKD will need kidney replacement therapy by the age of 50 to 60.

The only FDA-approved treatment for PKD is a drug called tolvaptan, which is poorly tolerated by most patients, Harroz said. Because this drug is taken orally, it can affect other organs in the body and cause problems such as frequent urination and liver dysfunction.

“We really need new treatments. [for PKD] It is well-tolerated and targets the root cause of the disease while correcting downstream signaling pathways that are dysregulated in the disease,” said Harlows. The research team identified that nearly all PKD patients have mutations in one of two proteins called polycystins, which are encoded by the genes PKD1 and PKD2. These proteins are important for normal cell function and growth control, as well as the polarity of the cells lining the kidneys, liver, and other organs.

“Our NEMO award-winning therapy actually targets the underlying mutation,” Harroz said. The research team plans to directly address the genetic basis of the disease through mRNA delivered using nanoparticles, a method that Hallows and Chung have been working on together for the past seven years. be. Nanoparticles have been used as a delivery system in medicine for many years, including for drugs to treat other diseases in other tissues, but the researchers’ method allows the delivered mRNA to be sent directly to the kidneys. It is unique in that it targets specific mutations found in most organs. Ideally, PKD patients should have no side effects in other parts of their body, Chung said.

Chung, a nanoparticle engineer, first began developing nanoparticles to treat heart disease as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago. She had an aha moment for the engineer when she realized that adjusting the size and surface would allow the nanoparticles to reach the kidneys.

“This was a coincidence that ultimately led to many new innovations in my group,” said Chung, whose team became famous for kidney nanomedicine after this discovery. “There’s just a lack of innovation when it comes to kidneys.”

When Chung transferred to USC, she reached out to Hallows. Mr. Hallows shared his interest in research on PKD, which he was already working on with Pastor Soler. The two have continued to work together ever since.

“The NEMO Award has the potential to be transformative,” said Chaplain Sorrell. “The fact that they are putting resources into supporting this kind of collaboration is really encouraging and really timely.”

Using innovation to treat growing health problems

The second-place winning USC team also sees the NEMO award as an opportunity to use innovation to address common and hard-to-treat diseases. According to the World Health Organization, by 2050, approximately 2.5 billion people worldwide will be living with some degree of hearing loss. At least 700 million people will require some form of rehabilitation services. There are many health problems that can lead to a diagnosis of hearing loss or dizziness, but Ogalai says this is also a problem with the inner ear, and there are few options for determining the root cause. “Currently we only have MRI and CT scans, but the resolution is too low to see cells and tissues,” he said.

Applegate and Ogarai used a technique called optical coherence tomography (OCT), commonly used by ophthalmologists to view the inside of the eye, to image the inner ears of human and mouse subjects. We have been working on solving this problem for many years. Although the technique has been very successful in mice, it is difficult to image human subjects because the human inner ear is blocked by a “thicker layer of bone,” Hsu said. This is problematic because the bone scatters light and distorts attempts to image the inner ear. “The reason we send telescopes into space is to avoid the distortions that occur when you try to see stars from the atmosphere,” Ogaray said. In humans, this would involve sticking a small endoscope into the inner ear, causing damage, he explained.

Recently, however, Hsu’s group has begun developing a computer imaging technique called scattering matrix tomography (SMT). This technique uses computer applications commonly used in astronomy to improve the resolution and depth of inner ear imaging.

The three NEMO award winners hope to join forces to use Hsu’s computational imaging techniques to overcome the limitations that Applegate and Oghalai have experienced with OCT technology.

“Until now, no one had been able to image the human inner ear at the required resolution,” Hsu said. “We want to be the first to do that.”

The research team is currently using preliminary techniques for this approach to scan patients’ outer ears, while continuing clinical trials on dead mice. The immediate goal is to move to live mice and, once Hsu’s algorithm is complete, to live humans. Applegate said their long-term goal is to develop a handheld, non-invasive SMT-OCT device that provides precise imaging from the ear canal. This medical device helps diagnose, create therapeutic interventions, and research new treatments for the treatment and prevention of hearing loss and dizziness.

“We are really grateful. [Keck Medicine of USC] We would like to thank the health system and Executive Vice President Shapiro’s office for organizing this, and the Nemirovsky family for donating the funds to support this award,” Ogaray said. “We’re really excited to be able to do this. We think this is going to help people.”

Partnership is the key to success

“We are thrilled that our faculty will receive NEMO award funding to advance their research on the human cochlea and polycystic kidney disease,” said Yannis C. Yorsos, dean of USC Viterbi. . “Partnerships with research collaborators at the Keck School of Medicine are key to the project’s success. Such interdisciplinary collaborations not only form an important element of the NEMO award, but also support the convergence of today’s health science and engineering disciplines. This is necessary as we move forward.”

The NEMO Award Steering Committee is committed to identifying exciting health engineering collaborations that are competitive for future follow-up funding from other sources and have the potential to improve health, health outcomes, and health delivery in the future. We are looking for applicants to submit proposals.

“Academia can sometimes be a bit isolating. [award] “It gives people an opportunity to share in a way that is not competitive but rather collaborative,” said Sherry Nemirovsky, whose brother and two of her three children also attended USC. The couple also made a gift in 2017 to establish the Nemirovsky Residential School at USC Village and to fund the Sherry and Ofer Nemirovsky President’s Chair. “My hope is that researchers will continue to have conversations across the school to find better mitigation methods to treat some of these terrible diseases that exist in the world. I think the possibilities are truly endless.” .”

[ad_2]

Source link