[ad_1]

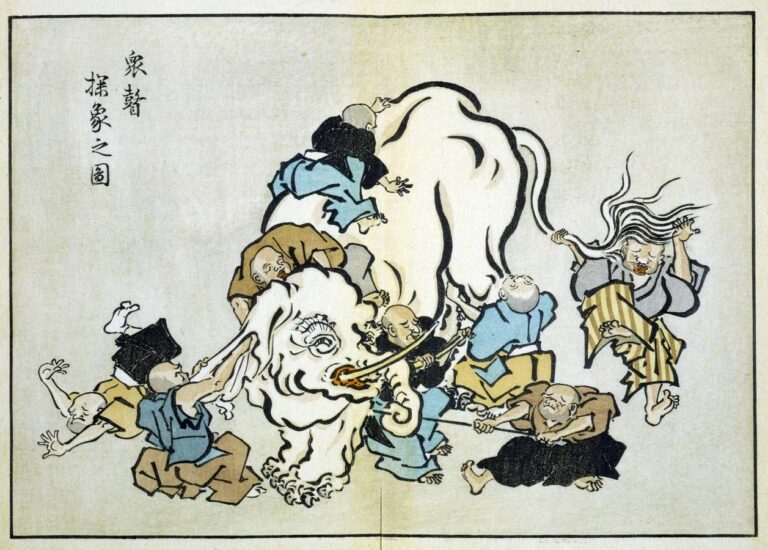

ESG funds, which are mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that consider environmental, social, and governance factors in investment decisions, are plagued by vitriol and misinformation. This is partly due to the amorphous nature of the term “ESG.” Reminds me of the parable of the blind man and the elephant. In James Baldwin’s retelling, six blind men touch various parts of an elephant and decide that the animal variously resembles a snake, a tree, a wall, a rope, and an elephant. Spear and fan. Baldwin concludes the story with the men fighting all day long. “Each believed he knew what the animal looked like. And each harshly criticized the other because they disagreed with his opinion. People with eyes sometimes do stupid things.” For us, ESG is the elephant in the room.

ESG has a long history. It evolved from centuries of ethical investing practices by religious groups that avoided “sinful” industries. To this day, ethics funds exist that screen out objectionable industries such as tobacco, alcohol, gambling, pornography, firearms, coal, and other fossil fuels. However, the term ‘ethical investing’ has become outdated and these types of funds are commonly known as ‘SRI’ (Socially Responsible Investment Funds).

“ESG” itself dates back to the 2004 United Nations Global Compact report. The report, co-sponsored by Europe’s biggest banks and financial institutions including Goldman Sachs GS and Morgan Stanley MS, makes little mention of ethics. Instead, good environmental and social practices and the corporate governance structures to successfully manage them are portrayed as money-making opportunities. “Companies with better ESG performance can increase shareholder value by better managing risks associated with emerging ESG issues and anticipating regulatory changes.” Access to new markets and costs By reducing this, you can understand consumer trends. ” This reconfiguration has allowed the financial industry to capitalize on consumer preferences for purchasing and investing in ethical and sustainable ways, while maintaining the financial industry’s reputation for robustness.

The idea that investors can use ESG analysis to manage the financial risk of environmental and social issues to their portfolio holdings has stood the test of time. Morningstar MORN asserts that “these factors – environmental, social, and governance – come down to the fundamentals of investing: risk.” The Global Risk Management Institute agrees: “ESG frameworks help companies move from a compliance-driven mindset to proactive risk mitigation strategies.” SRI may be about ethical investing, but ESG is about managing financial risk. is. Nevertheless, both approaches are lumped together under his ESG name because, although their intentions are different, their tactics can overlap. And the tactics are diverse. In addition to negative screening, there is also positive screening, which accumulates companies in the portfolio that exceed certain standards of good conduct. Some funds restrict investments in social themes such as healthcare. Some funds own a broad range of markets, but adjust the weighting of their portfolios to lean toward companies with better social and environmental characteristics. Some funds are also trying to use their holdings to persuade companies to change their behavior. Like elephants, ESG resembles many different things at once, and discussions about this topic are usually people talking to each other, each believing they know what the animal looks like. It is related to

In a polarized society, ESG funds are looked down upon by those who believe that these types of investments can undesirably change the behavior of the corporate sector and lead to threatening social change. His main criticisms are twofold. First, ESG investing violates fiduciary duties to focus solely on the economic interests of customers and retirement plan members, and instead prioritizes social and environmental policy objectives that are not economically significant. . Those who subscribe to this view are dabbling in the “ethical investing” part of ESG while ignoring the financial risk management aspects of the ESG construct. However, they do not claim that the risk management aspects are invalid. This is because the weight of evidence supports the claim that ESG analysis reliably reduces downside risk.

A second criticism is that ESG funds should be avoided because they offer lower returns than comparable funds that do not take into account environmental and social risk factors. The evidence here is not conclusive. But a simple analogy shows that this criticism is a dangerous red herring.

A risk mitigation strategy that we are all familiar with is insurance. We pay insurance premiums to reduce the risk of expensive repairs to our cars and homes. What do you think about insurance companies that offer free insurance policies or charge a subscription fee? Is it too good to be true? Free lunch? ESG funds should be considered similarly. We purchase ESG funds to reduce the downside risk of our investment portfolio. Higher returns and lower risks are the epitome of a free lunch, but we in the financial world insist that such things don’t exist. The trade-off between risk and return is the first thing you learn in an introduction to finance.

The third criticism comes not from the right, but from academics and former sustainability chiefs such as Tariq Fancy, Desiree Fixler and Stuart Kirk. This critique focuses on another area of the ESG construct: impact. The old idea that “doing good is doing well” means that ESG funds have a positive impact on society and the environment, allowing us to change the world while making money. However, there is serious debate about whether ESG funds actually make an impact or are just empty and sometimes fraudulent claims.

There are two main ways investors can change corporate behavior. One is ostensibly through portfolio allocation, which allows investors to expand sustainable industries and eliminate unsustainable industries by retaining capital from certain companies or industries and allocating capital to others. may be possible to reduce. The other is engagement, through persuasion behind closed doors and voting at companies’ annual meetings.

The problem with portfolio allocation is that most ESG funds hold public market stocks or bonds. These are traded between market participants without directly affecting the finances of the companies themselves. Some market participants argue that the level of buying and selling affects a company’s cost of capital, but there is little academic support for this idea. Owning an ESG fund may make you feel better about not owning stocks in companies you hate, and you may feel more secure that the downside risk built into your fund is lower, but you’re helping yourself. You shouldn’t feel that way. Earth and society, because you probably aren’t. Conservative opponents of ESG funds have little to fear in this regard.

However, there are signs of progress. Some UK pension funds are now implementing a philosophy backed by academic research: capitalize on equity but deny debt. ESG funds that follow this approach refuse to invest in undesirable corporate debt issues in the primary market, straining capital requirements, while using secondary market stocks to support sustainable shareholder resolutions, director elections, and payout decisions. It will be used to vote on resolutions. I don’t know if this kind of fund still exists, but if you do, joining it will meet all of your sustainable investing goals.

ESG can be a pointy spear of change, a fan providing comfort, or even a wall in the way. The current toxic political rhetoric around sustainable investing is a form of willful neglect and cannot be resolved unless we open our eyes to see the whole animal.

follow me LinkedIn.

[ad_2]

Source link